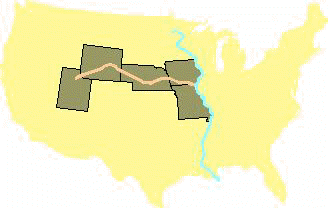

ACROSS IOWA IN 1846

The Iowa portion of the trek was the worst. The Mormons were not well prepared when they left during February and March of 1846. Brigham Young made arrangements to leave in spring however, due to the difficulties in Nauvoo the church leaders began the trek in early February.

By April 24th the pioneers had reached a place that they named Garden Grove, 144 miles west of Nauvoo. Here they established the first of several permanent camps between Nauvoo and Winter Quarters. In three weeks, they had broken 715 acres of tough prairie sod, built cabins, and established a community.

May 18th, they established Mount Pisgah, another permanent camp and resting place. There they built cabins and planted several thousand acres with peas, cucumbers, beans, corn, buckwheat, potatoes, pumpkins, and squash.

In the Council Bluffs area, between 1846 and 1853, the Mormons built at least fifty-five temporary and widely separated communities, farmed as much as 15,000 acres of land, and established three ferries. These numerous communities were established primarily to accommodate the thousands of Mormon emigrants, while they were either waiting to cross the Missouri River, or resting and preparing financially and physically to continue westward to Utah.

HISTORIC PERSPECTIVE

Mormon scholars have discovered at least ten “Uncommon Aspects of the Mormon Migration.”‘ These unique aspects are:

1. A religiously motivated migration

2. The economic status of the participants

3. Mormons did not employ professional guides

4. Non-frontiersmen were quickly transformed into pioneers

5. The migration of families

6. The Mormon Trail was a two-way road

7. The magnanimous aspect of the Mormon migration

8. The organization of Mormon wagon trains

9. Respect for life and death

10. The Mormon migration was a movement of a community.

In many ways the Mormons were very much like their contemporary Oregonians and Californians. West of the Missouri River they shared trails, campgrounds, ferries, triumphs, tragedies, and common trail experiences of the day, with thousands of other westering Americans.

The Saints used all kinds of wagons and carriages, but mostly they used ordinary reinforced farm wagons, which were about ten feet long, arched over by cloth or waterproof canvas that could be closed at each.

The pioneers used a variety of draft animals, especially horses, mules, and oxen. They often preferred the latter when they were available, for oxen had great strength and patience and were easy to keep; they did not balk at mud or quicksand, they required no expensive and complicated harness, and they could live better on the sparse grasses of the high plains.

THE PERPETUAL EMIGRATION FUND

The Perpetual Emigration Fund, was the biggest single enterprise undertaken by the Mormons in the nineteenth century. Begun in 1850, the idea was that the church would create a revolving (or perpetual) fund to aid the poor, especially the poor European emigrants. Those helped by the fund were expected to reimburse it after settling in the American West.

Perpetual Emigration Fund (PEF) agents in Europe chartered ships, or special sections of ships, at reduced fares, and other PEF agents in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, New Orleans, and St. Louis helped make travel arrangements, at reduced costs, for the overland journey to Utah.

Between 1850 and 1859 the fund brought 4,769 emigrants to Zion at a cost of $300,000. By the time of its demise in 1887, the fund had helped to emigrate more than 100,000 people, at a total cost of about $12,500,000.

ACROSS IOWA IN 1846

The Iowa portion of the trek was the worst. In spite of long preparations for quitting Nauvoo, the Mormons were not at all well prepared when they left during February and March of 1846.

By April 24th the pioneers had reached a place that they named Garden Grove, 144 miles west of Nauvoo. Here they established the first of several permanent camps between Nauvoo and Winter Quarters. In three weeks they had broken 715 acres of tough prairie sod, built cabins, and established a community.

Six days and about 35 miles later, they established Mount Pisgah, another permanent camp and resting place. There they built cabins and planted several thousand acres with peas, cucumbers, beans, corn, buckwheat, potatoes, pumpkins, and squash..

In the Council Bluffs area, between 1846 and 1853, the Mormons built at least fifty-five temporary and widely separated communities, farmed as much as 15,000 acres of land, and established three ferries. These numerous communities were established primarily to accommodate the thousands of Mormon emigrants, while they were either waiting to cross the Missouri River, or resting and preparing financially and physically to continue westward to Utah.

WINTER QUARTERS, 1846 (Nebraska)

In what is now Florence, Nebraska, the Saints finally built their Winter Quarters, the Mormon “Valley Forge.” Winter Quarters soon became a city of about 800 cabins, huts, caves, and sod, or “prairie marble,” hovels, and 3,483 people. At its height it had about 4,000 people. At least 400 died from various causes and are buried in the Winter Quarters’ cemetery.

WEST FROM THE MISSOURI RIVER WAGON EMIGRANTS: 1848-1860

The main difference between the pioneers of 1846-1847 and subsequent Mormon emigrants was that each year the trek became a little easier as a result of experience, established (and enforced) discipline, better roads, ferries, bridges, and the ever-increasing number of trailside services like blacksmithing, medical assistance, military installations, trading establishments, and the telegraph. Also, the leadership of post-1848 companies was turned over to lower-level leaders and even to missionaries returning from their fields of labor.

THE HANDCART EMIGRANTS 1856-1860

Brigham Young decided to try this supposedly faster, easier, cheaper, and certainly more unusual way to bring thousands of European converts to Salt Lake City. This famous experiment involved 2,962 people in 10 companies from 1856 through 1860.

The Mormon open carts varied in size and were made almost entirely out of wood. They were generally six or seven feet long, the width of a wide track wagon, and carried about 500 pounds of flour, bedding, extra clothing, cooking utensils, and a tent.

The Brigham Young Express Company 1856-1857

In 1856 the Mormon Church bid for and received a four-year contract for monthly mail service between Independence, Missouri, and Salt Lake City. The first permanent stations or settlements were set up at Genoa and on Deer Creek. Other stations were begun. The Mormons also made use of other existing stations.

The main objective was eventually to have stations every 50 miles–the daily distance attainable by mule teams. Such stations would also be aids to Mormon emigrants by stocking and providing grain and other basic supplies, where hay and other crops could be raised. Then suddenly the contract was canceled and the stations were closed for good.

CHURCH TEAM EMIGRANTS, 1860-1868

In 1860 Mormon leaders abandoned the handcart experiment in favor of the church ox-team method. This was done for two reasons: the discovery that loaded ox teams could be sent from Utah to the Missouri, pick up emigrants (and merchandise), and return to Utah in one season, and for better use of the church’s own resources, that is to save money.

By means of these “down and back” trips, the Mormons could export their own flour, beans, and bacon to supply the emigrants, and use the cash saved to buy and freight back needed supplies not available in Utah. Furthermore emigrants could be saved the expense and trouble of obtaining their own wagons or carts and draft animals to take them west.

The 2,200-mile round trip could be made in approximately six months. Each wagon was pulled by four yoke of oxen or mules and carried about 1,000 pounds of supplies. The teams were expected to reach the Missouri River at Florence in July and return with ten to twenty emigrants per wagon and all the freight they could load.

This system lasted for the period 1860-1868, and required about 2,000 wagons 2,500 teamsters, 17,550 oxen and brought approximately 20,500 emigrants to Utah.

Join Our Group

As a member of the National Mormon Trails Association, you join a community that celebrates the history and maintains the trail’s resonant voice.