On Monday, February 17th, Hiram B. Clawson and William C. Staines, who had been appointed Church emigration agents this season, left Salt Lake City for the East, with $27,000 to be used for the gathering of the poor. This year about $70,000 was raised for the emigration of the poor Saints, mainly from Great Britain, an extra effort being made on the part of the Saints in Utah for that purpose.

June 15.—On this and the two following days, the Church teams, about five hundred in number, sent to the terminus of the Union Pacific Railroad this season for the poor.

A most lamentable accident, however, befell his company at Green River on the 25th of June. They were crossing the river at Robison’s ferry, a large number of men with four yoke of oxen being on board the ferryboat. The river was very high, with a strong wind blowing. When fairly out in the river the boat began to dip water and became so heavy that it sank, breaking the guy rope and drifting down stream. The current swept away men, oxen and all loose timbers, mixed up in great confusion; men hanging to timbers and to the horns and tails of oxen as the wild waters carried them on. The boat, after the freight was swept from it, came to the surface. Mr. Molen and one or two others got aboard and threw out ropes to those in the water, encouraging the ones they could not reach to stick to their pieces of timber. They landed the boat about three miles down the river, between a small island and the main shore. On that island they found Julius Johnson, who had floated to that point on a piece of timber. When the roll was called, after the company had crossed, six men failed to respond—Thomas Yeates of Millville, Niels Christopherson and Peter Smith of Manti, Peter Neilson of Fairview, Chris Jensen and Chris Nebellah of Mount Pleasant—all supposed to be drowned.

Hyrum Weston Maughan. June 25. At Robinson’s Ferry, Green River, 6 of his companions were drowned by the upsetting of the ferry boat. He had stepped on the boat as it left the shore, but hearing the Captain say there were too many on the boat, he stepped off again. Their names were: Neils Christopherson and Peter Smith, of Manti; Peter Neilsen of Fairview; Christian Jensen and Christian Nybello of Mr. Pleasant; and Thomas Yeats of Millville, Cache Valley.

The Emerald Isle. There were 627 Scandinavians and 250 English emigrants under the direction of Elder Hans Jensen Hals as president, and counsellors J. Smith and John Forsberg, with Elder Peter Hansen acting as provision dealer. ( Before their departure from Liverpool there were words of encouragement and godspeed by Elders Franklin D. Richards, William B. Preston and Charles W. Penrose. On June 26, 1868, the ship stopped at Queenstown, Ireland, to obtain fresh water and other necessary items. It was here that some of the best men of the ship’s crew decided to remain, and from then on the entire journey was one of tragedy.)

Arriving at Queenstown, they remained three days, which proved anything but pleasant, as the emigrants were roughly treated by the ship’s crew. Seldom have Latter-day Saints suffered as much as did those who were the last to cross the Atlantic with sailships.

It was not only the rough handling of the Saints that made it so unpleasant and hard to bear, but the water became so rank that it caused many of the emigrants to sicken and die. In all, thirty-seven died, most of them children, from measles and bad water.

The ship anchored in New York Harbor, August 11th, and was quarantined for three days, where they were inspected, and thirty of the sick were taken to Staten Island for treatment, (others died in the hospital in New York.) and the rest were taken to Castle Garden, Aug. 14th. On the same day, the company sailed on a steamboat for the Hudson River, where they were stationed for two days while the baggage was weighed. While there a boy died. On the 17th, the railroad journey began from New York to Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago and Council Bluffs. They journeyed on the Union Pacific to Benton, 700 miles west of Omaha, arriving on the morning of the 25th. (They continued by train to Benton, Nebraska, where they were met by two ox team companies (Holman, Mumford) from Utah that were waiting to take them to Salt Lake City.) Here they were met by the Church wagons that took them to the Platte River, two miles from Benton. There they stayed until August 31.

The travel-weary Saints were still besieged with sickness, and thirty more gave up their lives between New York and Salt Lake City. The remainder of the emigrants arrived in Salt Lake City September 25, 1868.

This company concluded the emigration from Europe by sailship and oxteam

William Lindsey, Heber City. They caught up to the main body of the train at Echo Canyon. He writes of the wild oxen. He describes an incident of TAKING A DIFFERENT ROUTE BECAUSE A HEAVY TOLL WAS REQUIRED TO CROSS THE WEBER. Here they witnessed the bridge collapsing. Writes of the captain instructing the teamsters to be very careful with their health because there are no extra men. He describes the route in detail mentioning the following places: Bear River, Quaking asp Ridge, Muddy Bridge, Green River, Big Sandy, Little Sandy, Dry Sandy Pacific Springs South Pass, Sweetwater, Devils Gate, Whiskey Gap, and Rawlins, North Platte, and Benton. He comments on six men drowning crossing the Green River three weeks earlier. He writes in detail of the difficulty in getting the oxen across the Green River, nearly loosing some lives themselves. He writes of the good feed near Benton. Being the last train arriving, they had to wait for the last company of the season. He comments on the supplies they had taken including flour, bacon, beans. While waiting until September for the last company to arrive, their captain contracted the men to haul cords of wood to some of the railroad camps to raise money to purchase necessary supplies. He comments on have a lot of leisure time and filling it by singing songs, playing games and visiting other camps. He describes being in the midst of Indian country and taking turn guarding the oxen night an day. Dysentery broke out causing several, mostly grown men, to die within a few days and writes of burying them on the trail in shallow graves.

The heat was excessive and six individuals died of heat stroke aboard the train. He described the train journey passing through Canada, Council Bluffs, crossing the Missouri to Omaha. At Omaha, they boarded the Great Union Pacific Railroad of which he writes that it’s carriages are “really magnificent, and by far surpassing the finest first-class carriages in our own country.” It took two days to get organized for the journey.

Zebulon Jacobs, ret. miss., arriving in Chicago and staying all day and another night because of a misunderstanding, riding again in cattle cars while the sick and elderly rode in coach cars, passing through Illinois, transferring in Council Bluffs and ferrying to Omaha. Upon arriving in Omaha they discovered that no arrangements had been made for journeying from there, so he set out to make arrangements. The journey from Omaha to Cheyenne and finally to Laramie is described in detail.

Zebulon Jacobs on train travel: passing West Point, arriving at Albany and having to transfer to another rail line, transferring to cattle cars and box cars at Niagara Falls, passing through Canada, seeing the Great Lakes at Detroit, crossing the river there by ferry, boarding another train, arriving in Chicago and staying all day and another night because of a misunderstanding, riding again in cattle cars while the sick and elderly rode in coach cars, passing through Illinois, transferring in Council Bluffs and ferrying to Omaha. Upon arriving in Omaha they discovered that no arrangements had been made for journeying from there, so he set out to make arrangements. The journey from Omaha to Cheyenne and finally to Laramie is described in detail. His account of the journey by railroad includes mention of the deaths of several

extreme heat, people leaving the train when it stopped and not making it back in time, and many people sick including himself. Much of the sickness was caused by the heat. He felt he was walking in a dream and was trembling and when he touched the sick people’s flesh, it was like touching a hot iron. The railroad men on one line were rude and insulting while on another line they were kind. It was difficult to sleep in the jolting cattle cars and stuffy box cars, waking up scattered all over and having children and babies crying and others grunting, groaning and snoring. After Cheyenne he rode on top of a box car to sleep and get fresh air. The emigrants pitched a soldier and another man out of the train car because of meanness and insulting language. Another time, some brethren held down a sister possessed with an evil spirit to prevent her from jumping off the train and administered to her three different times. He discussed the emigrants’ discontent, discomfort, and at one point wrote that “all Hell broke loose.

Returning missionary, Harvey Cluff, with a Benton group wrote appointed to work with the railroad to oversee the company, obtain the tickets and handle all the affairs while travelling on the railroad. He appointed an elder on each car in the train to prevent contention among the people and ensure that there were morning and evening prayers. He was left behind in Rochester with all the passenger’s tickets. He boarded a freight train and met up with the company at Detroit. He mentioned going into Canada, on to Chicago and Omaha. He experienced difficulty in pacifying the emigrants in Omaha as there were only three passenger cars in which the women, children, and elderly were allowed to ride. The men rode in box cars. There were no accidents or deaths on the train, only “headaches, backaches, side aches, belly aches, leg aches, feet aches and conscience aches–nothing more.” All the luggage did not arrive at the same time and some of the company remained behind until it came and then caught up later waited in Benton for 7-8 days for their baggage

George Beard, “open box car crowded with the passengers from the ‘Emerald Isle'” He also describes stopping in Omaha seeing the emigrants “scattered around in a natural park just outside of the city… and as none of them had tents they all lay under the shade of the trees, cooking their own food for several days, waiting for a railroad car to take us to our destination”. He describes seeing a lone elderly Swedish woman die and being buried on the plains. He comments on the Scandinavians roasting green coffee. He also writes of seeing “Mexicans, Japs, Chinese, large-game hunters, trappers, Buffalo Bill, and he describes seeing his first Indian”. He describes Benton, Wyoming as being composed of shacks and tents occupied for saloons, stores, and living houses for people working on the Railroad. He describes in detail an incident at Benton City of the sheriff presenting Rose Taylor, who was on the train, with a warrant for her arrest. It was requested by her sister in who was in Benton. The captains of the emigrating companies waited until the case had been decided in court before proceeding on the journey. The courts decided to have her stay in Benton and a mob started out to burn and shoot up the wagons because they claimed the Mormons tried to force Miss Taylor to go with them to enter into polygamy. Captains Mumford and Holman (Gillespie in another account) formed a circle to defend themselves. The United States soldiers headed the mob back to Benton. He describes the teamsters as “happy, jolly, healthy-looking lot of men who used to entertain the immigrants at the campfires every night, dancing and singing and telling stories”. He writes of sleeping under the wagon with only one blanket, being stung on the finger by a scorpion and having a teamster treat the wound, seeing antelope, seeing a diamond back snake, and feeling the ground shake during a buffalo stampede. He writes that the trail was sandy and covered with sage brush and the grass had been eaten by animals before them. Because there was very little feed the captains decided to go over a new road through Whiskey Gap. He writes of having lice and describes his efforts at trying to “delouse” themselves.

He was assigned to help make railroad arrangements for the emigrants and was appointed chaplain of Capt. Holman’s train. He writes of handling business affairs with the railroad for emigrants and sending them on their way while remaining behind to finish business. After travelling to Chicago by train, he made arrangements to get the Scandinavian saints in better cars “they having rode in the poorest cars all the way from New York” He writes of Brother A. Larsen coming and helping the Saints cross the river on a steamer. He writes of the poor, uncomfortable and crowed cars in which they travelled on to Benton mentioning that several were very sick because of the heat and the ride. At Benton they were met by teams and he comments that they travelled to the North Platte and had to sleep the best they could without their luggage. He briefly comments on making preparations for the journey from Benton including washing clothes, raising tents, being busy with accounts, and making purchases for the company and distributing them from a wagon to the saints, and receiving instructions from Agent Pyper.

Hans Jorgenson (age 23) after a “deadly” trip at sea where 37 people died in less than two months,

Green River, the members of the Holman company were ferried by a Mr. Robinson from Pleasant Grove on his ferry. He refers to Whiskey Gap, Sweetwater, having no bedding and sleeping in the rain by a big fire, camping with no water, travelling where there was no feed for the oxen at times and other times feed being very plentiful

At Laramie they met Horace Eldredge, the emigrant agent who organized the companies.

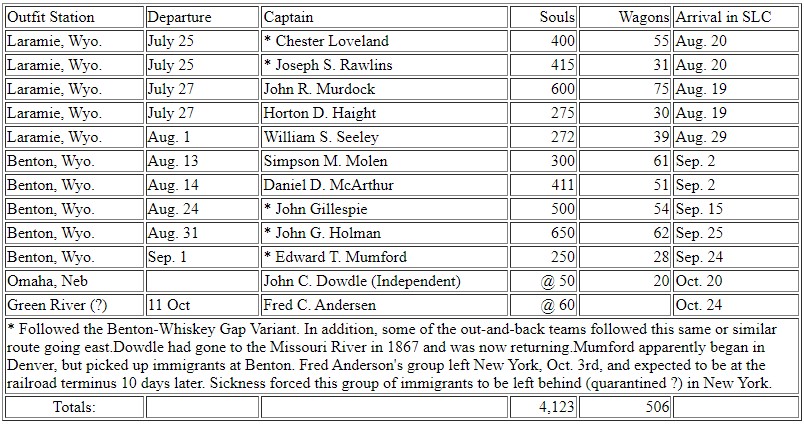

John Murdock wrote In order to avoid the railroad construction workers, Church authorities advised the out-and-back companies to “break a new road.” His company was too large to traverse the new road so he took the old Bitter Creek route. Joseph Rawlins’ and Chester Loveland’s companies encountered delays on their return. They freighted barrels of drinking water and companies competed to try to be the first to reach Salt Lake.

Celestial Knight said At Laramie, crowds came to stare at the Mormons as if they were animals. The mobs of people at Laramie became so abusive that the travel agents loaded the Mormons on cattle cars and started them westward. Thereafter they traveled by mule teams, horse teams, and walking. In general, the wagon train avoided railroad camps, traveling night and day to avoid the “rough element” and Indians present at the camps.

Fort Fred Steele and Benton, Wyoming (on the North Platte River, east of Rawlins off Interstate 80).

Fort Fred Steele was established June 20, 1868 and occupied until August 7, 1886 by soldiers who were sent by the U.S. Government to guard the railroad against attack from Indians. Colonel Richard I. Dodge, who selected this site on the west bank of the North Platte River, named the fort for Major General Frederick Steele, 20th U.S. Infantry, a Civil War hero. Although the fort at first resembled a tent city, Colonel Dodge’s military quartermaster quickly built the fort according to Army specifications. After the major Indian threat had passed, the War Department deactivated the post and transferred its troops to other military facilities throughout the United States. Only a guard was left to oversee this federal property.

Benton, 11 miles east of present day Rawlins at UP milepost 672.1, lasted only three months from July to September 1868, and attained a population of 3,000. Construction camps and end-of-track towns were often lawless sinks of crime. It had twenty-five saloons and five dance halls. During its brief existence, reputedly over 100 souls met their Maker in gunfights. One visitor referred to Benton as “nearer a repetition of Sodom and Gomorrah than any other place in America.” Fine alkali dust coated the streets and the wind seemingly never stopped. Water had to be hauled from the Platte River and could be sold for a dollar a barrel. Twice a day, trains arrived from the East bringing passengers and freight which then had to be unloaded and shipped further West in stagecoach or wagons. Despite its isolation, Benton had a newspaper, and in 1868 Ulysses S. Grant treated the folks to a speech during his Presidential campaign. Like many railroad towns, it exists no more.

Whiskey Gap is about 33 miles north of Rawlins. Whiskey Creek is the next creek east of Muddy Creek and Whiskey Gap is 4 miles southeast of the Muddy Gap intersection (at the base of the Ferris Mountains), or straight east across Highway 287. The first official prohibition enforcement action on record in the U.S., happened in 1862 at Whiskey Gap. This happened when a Major Jack O’Farrell commander of “A” Company Eleventh Ohio Cavalry (from Fort Halleck) gave an order stating ” All wagon trains containing whiskey are to be condemned and destroyed”.

Benton to Bitter Creek, 88 1/2 miles west (by train)

Levi Wolstenholme, Sr. In the year of 1868 I went back after immigrants. I was now 19 years old. I drove four yoke of oxen and took a great pride in my team and was repaid by receiving many compliments concerning them. Captain Caldwell was the captain of the company going out and Captain John Gillespie was our captain back. We had to drive back to North Platte, Nebraska. That was then the terminus of the U. P. Railroad. We went to a little railroad town named Benton. Here we waited six weeks for the immigrants. I did not enjoy the trip as I was sick most of the time.

Francis De La Haye Horman sailing vessel Constitution, with 457 British, Swiss and German Saints, [p.467] with Harvey H. Cluff in charge. I was baptized in the Atlantic Ocean on the 25th of March 1865, being 9 1/2 years of age. Elder Cave baptized me and Father confirmed me the 27th of March 1865.

Our Pioneer Heritage, Vol. 9, p.467

We arrived in New York August 5, 1868, and continued our journey by train to Benton, Wyoming. The freight train that our trunks and bedding were in got wrecked so we lost one trunk of clothes. We had to wait several days for our goods to reach us, and had to sleep in what clothes we carried with us on the train for about 19 days. We left Benton on the 24th of August in Capt. John Gillespie’s ox train of 54 wagons and about 500 immigrants and arrived in Salt Lake City on the 15th of September. We camped in the tithing yard where the Hotel Utah now stands. We were assigned to go to Tooele, so in about two days we landed in Tooele City to make our home. When we arrived in Tooele City, Utah, we were all re-baptized and confirmed in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This was done so that the ward would have a record.

Margaret Robertson Salmon. I was born in 1858, May 21, at Barhead, Renfrewshire, Scotland. Castle Gardens, N.Y. Aug. 11, where we boarded the train for Omaha. Arriving at Omaha, we camped at Fort Benton, awaiting Captains Mumford and Holman, who were to bring the wagons to take us to Utah.

Joseph Wright, steamship “Colorado,” July 14, 1868. We arrived in New York July 28, 1868, and at Benton, the terminus of the Union Pacific railroad, Aug. 7, 1868, Here we camped on the North Platte [p.468] river about one week. We left Benton Aug. 14th in Daniel D. McArthur’s ox-train of 61 wagons and 411 persons

Numerous immigrants and teamsters referred to Benton as Ft. Benton, which was wrong. There is a Ft. Benton in Montana. Benton city consisted of tents, in or nearby Ft. Fred Steele

Join Our Group

As a member of the National Mormon Trails Association, you join a community that celebrates the history and maintains the trail’s resonant voice.